Composition vs Inheritance in React: Why Composition Wins

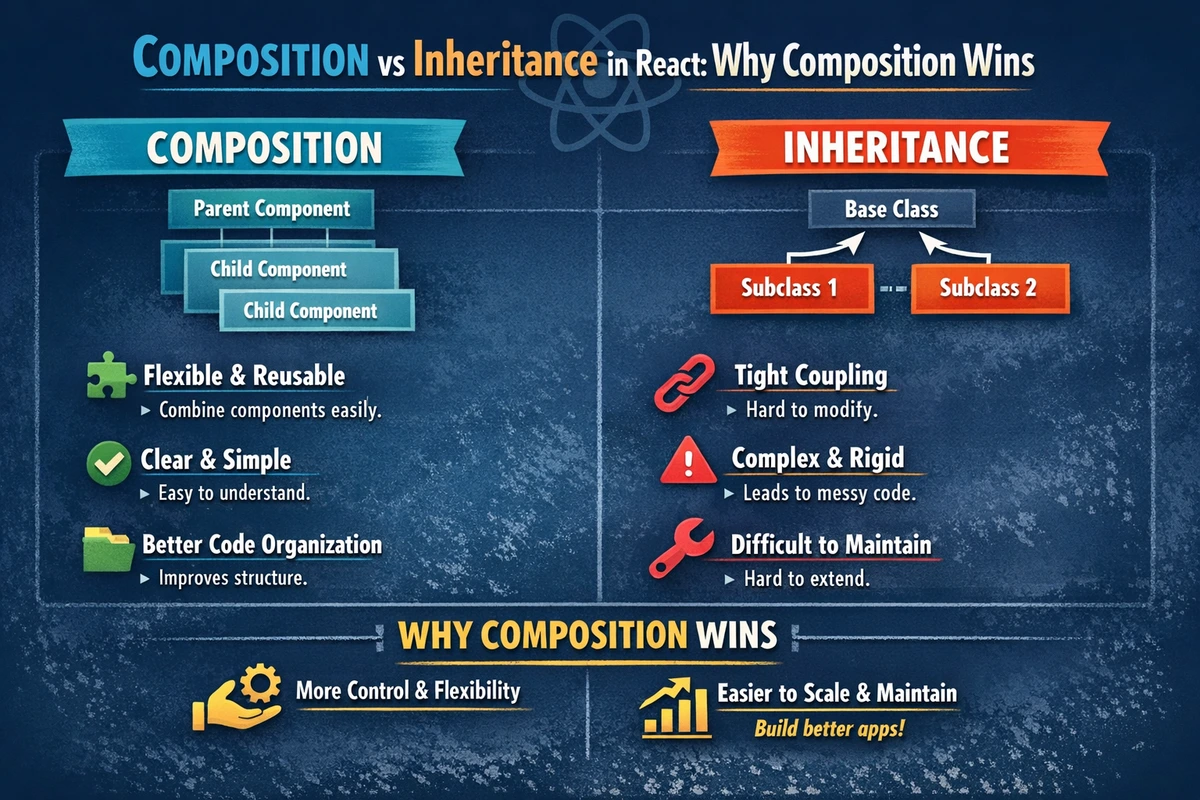

When you're building React applications, you'll inevitably face a fundamental design question: should you use inheritance or composition to share behavior between components? This decision shapes how maintainable, testable, and flexible your codebase becomes. React's component model was deliberately designed with composition as its primary mechanism, and there's a reason Facebook engineers moved away from inheritance entirely. Let's explore why composition isn't just a preference—it's the right architectural choice for building scalable React applications.

Table of Contents

- Understanding the Core Difference

- Why React Chose Composition

- Composition Patterns in Action

- Advanced Composition Techniques

- Real-World Scenarios

- Common Pitfalls and Solutions

- FAQ

Understanding the Core Difference

Before diving into React-specific patterns, let's establish what inheritance and composition fundamentally mean in object-oriented programming, and how they translate to component architecture.

What is Inheritance?

Inheritance creates a hierarchical relationship where a child class inherits properties and methods from a parent class. In classical OOP, you'd write something like this in a non-React context:

// Classical inheritance pattern (DON'T DO THIS IN REACT)

class Button extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = { isLoading: false };

}

setLoading(value) {

this.setState({ isLoading: value });

}

render() {

return <button disabled={this.state.isLoading}>Click me</button>;

}

}

// Child class inherits from Button

class SubmitButton extends Button {

handleClick() {

this.setLoading(true);

// API call logic

}

render() {

// Must override entire render method

return <button onClick={this.handleClick} disabled={this.state.isLoading}>

{this.state.isLoading ? 'Submitting...' : 'Submit'}

</button>;

}

}This approach has several problems in React:

- Tight Coupling: The child component is tightly bound to the parent's implementation details

- Fragile Base Class: Changes to the parent class can break unexpected child classes

- Render Method Conflicts: You can't easily share rendering logic without duplicating code

- Limited Reusability: Each new variant requires a new subclass

What is Composition?

Composition builds functionality by combining smaller, focused components. Instead of inheritance hierarchies, you assemble components together, passing behavior through props:

// Composition pattern (PREFERRED)

interface ButtonProps {

isLoading?: boolean;

onClick?: () => void;

children: ReactNode;

}

function Button({ isLoading, onClick, children }: ButtonProps) {

return (

<button onClick={onClick} disabled={isLoading}>

{children}

</button>

);

}

// Reuse Button with different configurations

function SubmitButton({ onSubmit }: { onSubmit: () => Promise<void> }) {

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const handleSubmit = async () => {

setIsLoading(true);

try {

await onSubmit();

} finally {

setIsLoading(false);

}

};

return (

<Button isLoading={isLoading} onClick={handleSubmit}>

{isLoading ? 'Submitting...' : 'Submit'}

</Button>

);

}Notice how the second example doesn't create new classes—it simply uses the Button component with different props. This is composition, and it's the React way.

Why React Chose Composition

React's core philosophy is built around composition for specific, well-researched reasons. Understanding these reasons helps you make better architectural decisions in your own code.

1. The Evolution of Component Patterns

React didn't always emphasize composition over inheritance. Early React codebases (2013-2015) often used inheritance, especially with mixins. However, as applications grew more complex, teams discovered that inheritance led to:

- Mixin Hell: Multiple mixins created naming conflicts and unclear behavior sources

- Fragility: Deep inheritance chains made refactoring risky

- Testing Difficulties: Inheritance made unit testing harder because you had to understand the entire inheritance hierarchy

Facebook's engineers, working on massive codebases like the Facebook website itself, realized composition scaled better. This led to the official recommendation: composition over inheritance became React's philosophy around React 15-16.

2. Component Responsibilities Are Clearer

With composition, each component has a single, well-defined responsibility:

// ✅ GOOD: Each component has one job

interface LoadingButtonProps {

isLoading: boolean;

onClick: () => void;

children: ReactNode;

}

function LoadingButton({ isLoading, onClick, children }: LoadingButtonProps) {

return <button onClick={onClick} disabled={isLoading}>{children}</button>;

}

interface UseAsyncSubmitProps {

onSubmit: () => Promise<void>;

children: (state: { isLoading: boolean }) => ReactNode;

}

function UseAsyncSubmit({ onSubmit, children }: UseAsyncSubmitProps) {

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const handleSubmit = async () => {

setIsLoading(true);

try {

await onSubmit();

} finally {

setIsLoading(false);

}

};

return children({ isLoading });

}

// Combine them: UseAsyncSubmit handles logic, LoadingButton handles rendering

function SubmitButton() {

return (

<UseAsyncSubmit onSubmit={async () => { /* API call */ }}>

{({ isLoading }) => (

<LoadingButton isLoading={isLoading}>

Submit Form

</LoadingButton>

)}

</UseAsyncSubmit>

);

}3. Props Flow Is Predictable

With inheritance, understanding data flow requires tracking through the entire class hierarchy. With composition, props flow downward in a single direction, making the data path transparent:

// ✅ Composition: Clear data flow

<Parent data="from-parent">

<Child /> {/* gets data via props */}

<Sibling /> {/* gets same data via props */}

</Parent>

// ❌ Inheritance: Unclear where behavior comes from

class Parent extends BaseComponent {}

class Child extends Parent {} // What does Child inherit? Look at Parent, then BaseComponent...4. Composition Enables React's Modern Architecture

React 16.8 introduced hooks, which require composition-based thinking. You can't use hooks in class-based inheritance hierarchies effectively. The modern React ecosystem (custom hooks, context, suspense) is entirely built on composition patterns.

Composition Patterns in Action

Now let's explore the practical patterns React developers use to compose components effectively. Each pattern addresses different use cases and levels of complexity.

Pattern 1: Props Passing (The Simplest Approach)

The most straightforward composition pattern is passing behavior through props:

TypeScript Version

import { ReactNode } from 'react';

interface CardProps {

title: string;

children: ReactNode;

onAction?: () => void;

}

function Card({ title, children, onAction }: CardProps) {

return (

<div className="card p-6 rounded-lg shadow">

<h2 className="text-lg font-bold mb-4">{title}</h2>

<div className="card-content mb-4">{children}</div>

{onAction && (

<button

onClick={onAction}

className="px-4 py-2 bg-blue-500 text-white rounded hover:bg-blue-600"

>

Action

</button>

)}

</div>

);

}

// Usage - props are explicitly passed

function UserProfile({ userId }: { userId: string }) {

const handleDelete = () => {

console.log('Delete user:', userId);

};

return (

<Card

title="User Profile"

onAction={handleDelete}

>

<p>User information here</p>

</Card>

);

}JavaScript Version

function Card({ title, children, onAction }) {

return (

<div className="card p-6 rounded-lg shadow">

<h2 className="text-lg font-bold mb-4">{title}</h2>

<div className="card-content mb-4">{children}</div>

{onAction && (

<button

onClick={onAction}

className="px-4 py-2 bg-blue-500 text-white rounded hover:bg-blue-600"

>

Action

</button>

)}

</div>

);

}

function UserProfile({ userId }) {

const handleDelete = () => {

console.log('Delete user:', userId);

};

return (

<Card

title="User Profile"

onAction={handleDelete}

>

<p>User information here</p>

</Card>

);

}When to use this pattern: For simple component relationships with a small number of configurable features. Props passing is the foundation of React and should be your go-to approach.

Pattern 2: Render Props (Inverting Control)

When a parent component needs to let children define their own rendering logic while sharing state, render props are powerful. Instead of inheriting behavior, a component receives a function as a prop that defines what to render:

TypeScript Version

import { useState, ReactNode } from 'react';

interface DataFetcherProps {

url: string;

children: (state: {

data: unknown;

isLoading: boolean;

error: Error | null;

}) => ReactNode;

}

function DataFetcher({ url, children }: DataFetcherProps) {

const [data, setData] = useState<unknown>(null);

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(true);

const [error, setError] = useState<Error | null>(null);

// Use effect with proper cleanup

useEffect(() => {

let isMounted = true;

const fetchData = async () => {

try {

const response = await fetch(url);

if (!response.ok) throw new Error(`HTTP ${response.status}`);

const result = await response.json();

if (isMounted) setData(result);

} catch (err) {

if (isMounted) setError(err instanceof Error ? err : new Error('Unknown error'));

} finally {

if (isMounted) setIsLoading(false);

}

};

fetchData();

// Cleanup function prevents state updates after unmount

return () => {

isMounted = false;

};

}, [url]);

// Pass state to render function - child controls how to display it

return children({ data, isLoading, error });

}

// Usage: Each component controls its own rendering

function UsersList() {

return (

<DataFetcher url="/api/users">

{({ data, isLoading, error }) => {

if (isLoading) return <div>Loading users...</div>;

if (error) return <div>Error: {error.message}</div>;

if (!Array.isArray(data)) return null;

return (

<ul>

{data.map((user: any) => (

<li key={user.id}>{user.name}</li>

))}

</ul>

);

}}

</DataFetcher>

);

}

function PostsList() {

return (

<DataFetcher url="/api/posts">

{({ data, isLoading, error }) => {

if (isLoading) return <div className="spinner" />;

if (error) return <div className="error-banner">{error.message}</div>;

if (!Array.isArray(data)) return null;

return (

<div className="posts-grid">

{data.map((post: any) => (

<article key={post.id} className="post-card">

<h3>{post.title}</h3>

<p>{post.excerpt}</p>

</article>

))}

</div>

);

}}

</DataFetcher>

);

}JavaScript Version

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function DataFetcher({ url, children }) {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(true);

const [error, setError] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

let isMounted = true;

const fetchData = async () => {

try {

const response = await fetch(url);

if (!response.ok) throw new Error(`HTTP ${response.status}`);

const result = await response.json();

if (isMounted) setData(result);

} catch (err) {

if (isMounted) setError(err);

} finally {

if (isMounted) setIsLoading(false);

}

};

fetchData();

return () => {

isMounted = false;

};

}, [url]);

return children({ data, isLoading, error });

}

function UsersList() {

return (

<DataFetcher url="/api/users">

{({ data, isLoading, error }) => {

if (isLoading) return <div>Loading users...</div>;

if (error) return <div>Error: {error.message}</div>;

return (

<ul>

{data.map((user) => (

<li key={user.id}>{user.name}</li>

))}

</ul>

);

}}

</DataFetcher>

);

}When to use this pattern: When you want to share stateful logic but let different components render differently. Render props are particularly useful for sharing async operations, form state, or animation logic.

Pattern 3: Higher-Order Components (HOCs)

A Higher-Order Component wraps a component and enhances it with additional functionality. It's a function that takes a component and returns an enhanced version:

TypeScript Version

import { ComponentType, useState, ReactNode } from 'react';

interface WithLoadingProps {

isLoading: boolean;

}

// HOC that adds loading functionality

function withLoading<P extends WithLoadingProps>(

Component: ComponentType<P>

) {

return function WithLoadingComponent(

props: Omit<P, 'isLoading'> & { isLoading: boolean }

) {

if (props.isLoading) {

return <div className="loader">Loading...</div>;

}

// Pass remaining props to wrapped component

return <Component {...(props as P)} />;

};

}

interface ButtonProps extends WithLoadingProps {

onClick: () => void;

children: ReactNode;

}

function Button({ isLoading, onClick, children }: ButtonProps) {

return (

<button

onClick={onClick}

disabled={isLoading}

className="px-4 py-2 bg-blue-500 text-white rounded disabled:opacity-50"

>

{children}

</button>

);

}

// Enhanced button component

const LoadingButton = withLoading(Button);

// Usage

function App() {

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const handleClick = async () => {

setIsLoading(true);

try {

await fetch('/api/action');

} finally {

setIsLoading(false);

}

};

return (

<LoadingButton isLoading={isLoading} onClick={handleClick}>

Click me

</LoadingButton>

);

}JavaScript Version

import { useState } from 'react';

function withLoading(Component) {

return function WithLoadingComponent(props) {

if (props.isLoading) {

return <div className="loader">Loading...</div>;

}

return <Component {...props} />;

};

}

function Button({ isLoading, onClick, children }) {

return (

<button

onClick={onClick}

disabled={isLoading}

className="px-4 py-2 bg-blue-500 text-white rounded disabled:opacity-50"

>

{children}

</button>

);

}

const LoadingButton = withLoading(Button);

function App() {

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const handleClick = async () => {

setIsLoading(true);

try {

await fetch('/api/action');

} finally {

setIsLoading(false);

}

};

return (

<LoadingButton isLoading={isLoading} onClick={handleClick}>

Click me

</LoadingButton>

);

}When to use this pattern: HOCs are useful for cross-cutting concerns like authentication checks, theme providers, or analytics tracking. However, modern hooks often provide cleaner alternatives—consider custom hooks first.

Pattern 4: Custom Hooks (The Modern Approach)

With the introduction of hooks in React 16.8, custom hooks became the preferred way to share stateful logic across components. This is often cleaner than HOCs or render props:

TypeScript Version

import { useState, useCallback } from 'react';

interface UseFormState {

values: Record<string, string>;

errors: Record<string, string>;

}

interface UseFormReturn {

values: Record<string, string>;

errors: Record<string, string>;

setValue: (name: string, value: string) => void;

setError: (name: string, error: string) => void;

reset: () => void;

}

function useForm(initialValues: Record<string, string>): UseFormReturn {

const [state, setState] = useState<UseFormState>({

values: initialValues,

errors: {},

});

const setValue = useCallback((name: string, value: string) => {

setState(prev => ({

...prev,

values: { ...prev.values, [name]: value },

errors: { ...prev.errors, [name]: '' }, // Clear error when user corrects

}));

}, []);

const setError = useCallback((name: string, error: string) => {

setState(prev => ({

...prev,

errors: { ...prev.errors, [name]: error },

}));

}, []);

const reset = useCallback(() => {

setState({ values: initialValues, errors: {} });

}, [initialValues]);

return { ...state, setValue, setError, reset };

}

// Usage: Components use the hook directly

function LoginForm() {

const form = useForm({ email: '', password: '' });

const handleSubmit = (e: React.FormEvent) => {

e.preventDefault();

// Validation logic

if (!form.values.email) {

form.setError('email', 'Email is required');

return;

}

// Submit form

console.log('Submit:', form.values);

};

return (

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

<input

type="email"

value={form.values.email}

onChange={(e) => form.setValue('email', e.target.value)}

className="border p-2"

/>

{form.errors.email && <p className="text-red-500">{form.errors.email}</p>}

<input

type="password"

value={form.values.password}

onChange={(e) => form.setValue('password', e.target.value)}

className="border p-2"

/>

<button type="submit" className="px-4 py-2 bg-blue-500 text-white rounded">

Login

</button>

</form>

);

}

function RegistrationForm() {

const form = useForm({ email: '', password: '', confirm: '' });

// Can use the same hook with different initial values

// This is the power of composition with hooks!

return <form>{/* Form JSX */}</form>;

}JavaScript Version

import { useState, useCallback } from 'react';

function useForm(initialValues) {

const [state, setState] = useState({

values: initialValues,

errors: {},

});

const setValue = useCallback((name, value) => {

setState(prev => ({

...prev,

values: { ...prev.values, [name]: value },

errors: { ...prev.errors, [name]: '' },

}));

}, []);

const setError = useCallback((name, error) => {

setState(prev => ({

...prev,

errors: { ...prev.errors, [name]: error },

}));

}, []);

const reset = useCallback(() => {

setState({ values: initialValues, errors: {} });

}, [initialValues]);

return { ...state, setValue, setError, reset };

}

function LoginForm() {

const form = useForm({ email: '', password: '' });

const handleSubmit = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

if (!form.values.email) {

form.setError('email', 'Email is required');

return;

}

console.log('Submit:', form.values);

};

return (

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

<input

type="email"

value={form.values.email}

onChange={(e) => form.setValue('email', e.target.value)}

/>

{form.errors.email && <p>{form.errors.email}</p>}

<button type="submit">Login</button>

</form>

);

}When to use this pattern: Custom hooks are the modern way to share stateful logic. They're simpler to understand than HOCs and more flexible than render props. Prefer hooks for new code.

Advanced Composition Techniques

As your applications grow, you'll encounter scenarios where basic composition isn't enough. These advanced techniques address complex architectural challenges.

Compound Components Pattern

Compound components allow a parent to manage shared state while child components have access to that state through composition:

TypeScript Version

import { createContext, useContext, ReactNode, useState } from 'react';

interface TabContextType {

activeTab: string;

setActiveTab: (id: string) => void;

}

const TabContext = createContext<TabContextType | undefined>(undefined);

interface TabsProps {

children: ReactNode;

defaultActive: string;

}

function Tabs({ children, defaultActive }: TabsProps) {

const [activeTab, setActiveTab] = useState(defaultActive);

return (

<TabContext.Provider value={{ activeTab, setActiveTab }}>

<div className="tabs">{children}</div>

</TabContext.Provider>

);

}

interface TabListProps {

children: ReactNode;

}

function TabList({ children }: TabListProps) {

return <div className="tab-list">{children}</div>;

}

interface TabProps {

id: string;

children: ReactNode;

}

function Tab({ id, children }: TabProps) {

const context = useContext(TabContext);

if (!context) throw new Error('Tab must be used within Tabs');

return (

<button

onClick={() => context.setActiveTab(id)}

className={context.activeTab === id ? 'active' : ''}

>

{children}

</button>

);

}

interface TabPanelsProps {

children: ReactNode;

}

function TabPanels({ children }: TabPanelsProps) {

return <div className="tab-panels">{children}</div>;

}

interface TabPanelProps {

id: string;

children: ReactNode;

}

function TabPanel({ id, children }: TabPanelProps) {

const context = useContext(TabContext);

if (!context) throw new Error('TabPanel must be used within Tabs');

return context.activeTab === id ? <div className="tab-panel">{children}</div> : null;

}

// Usage - Clear, declarative API

function Settings() {

return (

<Tabs defaultActive="general">

<TabList>

<Tab id="general">General</Tab>

<Tab id="privacy">Privacy</Tab>

<Tab id="notifications">Notifications</Tab>

</TabList>

<TabPanels>

<TabPanel id="general">

<h2>General Settings</h2>

{/* content */}

</TabPanel>

<TabPanel id="privacy">

<h2>Privacy Settings</h2>

{/* content */}

</TabPanel>

<TabPanel id="notifications">

<h2>Notification Settings</h2>

{/* content */}

</TabPanel>

</TabPanels>

</Tabs>

);

}JavaScript Version

import { createContext, useContext, useState } from 'react';

const TabContext = createContext(undefined);

function Tabs({ children, defaultActive }) {

const [activeTab, setActiveTab] = useState(defaultActive);

return (

<TabContext.Provider value={{ activeTab, setActiveTab }}>

<div className="tabs">{children}</div>

</TabContext.Provider>

);

}

function TabList({ children }) {

return <div className="tab-list">{children}</div>;

}

function Tab({ id, children }) {

const context = useContext(TabContext);

if (!context) throw new Error('Tab must be used within Tabs');

return (

<button

onClick={() => context.setActiveTab(id)}

className={context.activeTab === id ? 'active' : ''}

>

{children}

</button>

);

}

function TabPanels({ children }) {

return <div className="tab-panels">{children}</div>;

}

function TabPanel({ id, children }) {

const context = useContext(TabContext);

if (!context) throw new Error('TabPanel must be used within Tabs');

return context.activeTab === id ? <div className="tab-panel">{children}</div> : null;

}

function Settings() {

return (

<Tabs defaultActive="general">

<TabList>

<Tab id="general">General</Tab>

<Tab id="privacy">Privacy</Tab>

</TabList>

<TabPanels>

<TabPanel id="general">

<h2>General Settings</h2>

</TabPanel>

<TabPanel id="privacy">

<h2>Privacy Settings</h2>

</TabPanel>

</TabPanels>

</Tabs>

);

}Real-World Scenarios

Understanding composition patterns in isolation is valuable, but let's see how they combine in real production scenarios from companies like Alibaba and ByteDance, where these patterns handle millions of users.

Scenario: Building a Flexible Modal System

Modern applications need modals that work across different use cases—forms, confirmations, alerts—without duplication:

TypeScript Version

import { ReactNode, useState, useCallback } from 'react';

interface UseModalReturn {

isOpen: boolean;

open: () => void;

close: () => void;

}

function useModal(initialOpen = false): UseModalReturn {

const [isOpen, setIsOpen] = useState(initialOpen);

const open = useCallback(() => setIsOpen(true), []);

const close = useCallback(() => setIsOpen(false), []);

return { isOpen, open, close };

}

interface ModalProps {

isOpen: boolean;

onClose: () => void;

title: string;

children: ReactNode;

}

function Modal({ isOpen, onClose, title, children }: ModalProps) {

if (!isOpen) return null;

return (

<div className="modal-overlay" onClick={onClose}>

<div className="modal-content" onClick={(e) => e.stopPropagation()}>

<div className="modal-header">

<h2>{title}</h2>

<button onClick={onClose} className="close-btn">×</button>

</div>

<div className="modal-body">{children}</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

// Composition: Combine hooks and components

function DeleteConfirmation() {

const modal = useModal();

const handleConfirm = async () => {

// API call to delete

await fetch('/api/delete', { method: 'POST' });

modal.close();

};

return (

<>

<button onClick={modal.open} className="delete-btn">

Delete Item

</button>

<Modal

isOpen={modal.isOpen}

onClose={modal.close}

title="Confirm Deletion"

>

<p>Are you sure? This action cannot be undone.</p>

<div className="modal-actions">

<button onClick={modal.close} className="btn-cancel">

Cancel

</button>

<button onClick={handleConfirm} className="btn-danger">

Delete

</button>

</div>

</Modal>

</>

);

}

// Same Modal component, different use case

function UserFormModal() {

const modal = useModal();

const handleSubmit = (formData: Record<string, string>) => {

// Save user

modal.close();

};

return (

<>

<button onClick={modal.open}>Add User</button>

<Modal

isOpen={modal.isOpen}

onClose={modal.close}

title="Add New User"

>

{/* Form component here */}

</Modal>

</>

);

}JavaScript Version

import { useState, useCallback } from 'react';

function useModal(initialOpen = false) {

const [isOpen, setIsOpen] = useState(initialOpen);

const open = useCallback(() => setIsOpen(true), []);

const close = useCallback(() => setIsOpen(false), []);

return { isOpen, open, close };

}

function Modal({ isOpen, onClose, title, children }) {

if (!isOpen) return null;

return (

<div className="modal-overlay" onClick={onClose}>

<div className="modal-content" onClick={(e) => e.stopPropagation()}>

<div className="modal-header">

<h2>{title}</h2>

<button onClick={onClose}>×</button>

</div>

<div className="modal-body">{children}</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

function DeleteConfirmation() {

const modal = useModal();

const handleConfirm = async () => {

await fetch('/api/delete', { method: 'POST' });

modal.close();

};

return (

<>

<button onClick={modal.open} className="delete-btn">

Delete Item

</button>

<Modal

isOpen={modal.isOpen}

onClose={modal.close}

title="Confirm Deletion"

>

<p>Are you sure? This action cannot be undone.</p>

<div className="modal-actions">

<button onClick={modal.close} className="btn-cancel">

Cancel

</button>

<button onClick={handleConfirm} className="btn-danger">

Delete

</button>

</div>

</Modal>

</>

);

}This demonstrates composition in action: useModal provides the logic, Modal provides the structure, and consuming components combine them for their specific use case. No inheritance needed.

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

Even with composition, you can run into problems. Let's address the most common ones:

Pitfall 1: Prop Drilling

When props pass through multiple intermediate components, it becomes hard to maintain:

// ❌ BAD: Props drilling through multiple levels

function Page({ userId }: { userId: string }) {

return <Section userId={userId} />;

}

function Section({ userId }: { userId: string }) {

return <Card userId={userId} />;

}

function Card({ userId }: { userId: string }) {

return <UserInfo userId={userId} />;

}

// ✅ GOOD: Use Context API to skip levels

import { createContext, useContext } from 'react';

const UserContext = createContext<string | null>(null);

function Page({ userId }: { userId: string }) {

return (

<UserContext.Provider value={userId}>

<Section />

</UserContext.Provider>

);

}

function Section() {

return <Card />; // No userId prop needed

}

function Card() {

return <UserInfo />; // No userId prop needed

}

function UserInfo() {

const userId = useContext(UserContext);

return <div>User: {userId}</div>;

}Pitfall 2: Wrapper Hell

Too many nested component wrappers make code hard to debug:

// ❌ BAD: Multiple HOCs create wrapper hell

const Enhanced = withTheme(withAuth(withRouter(MyComponent)));

// ✅ GOOD: Use custom hooks to flatten hierarchy

function MyComponent() {

const theme = useTheme();

const user = useAuth();

const router = useRouter();

// Component directly uses hooks without nesting

return <div>{/* content */}</div>;

}Pitfall 3: Breaking Composition with Over-Abstraction

Trying to compose too much can create unmaintainable abstractions:

// ❌ OVERLY ABSTRACT: Hard to understand what it does

const withLoadingAndErrorAndCachingAndRetry = (Component) => {

return (props) => {

// 300 lines of complex logic

};

};

// ✅ SIMPLE: Each piece has clear purpose

function useDataFetching(url: string) {

// Just handles fetching

}

function DataFetcher({ children, url }: {children: any, url: string}) {

const data = useDataFetching(url);

return children(data);

}

// Caching, retry, etc. are separate concernsFAQ

Q: Is inheritance ever appropriate in React?

A: Inheritance in React is almost always inappropriate. Even in edge cases where you might consider it (like sharing complex component logic), hooks, HOCs, or render props provide better solutions. The React team explicitly recommends against inheritance for component behavior. The only time inheritance is appropriate is when extending library base classes for specific framework reasons, which is rare.

Q: Custom hooks vs HOCs—which should I use?

A: Custom hooks are almost always better. They're simpler to understand, easier to compose, and don't cause wrapper hell. Use HOCs only when you specifically need to augment a component's rendering (like adding analytics or theme wrapping), which is increasingly rare with modern patterns.

Q: How do I choose between render props and compound components?

A: Use render props when you're sharing stateful logic that multiple different UIs might need. Use compound components when you have a family of tightly-related components (like Tabs, AccordionItem, etc.) that share state. Compound components provide a cleaner, more declarative API when the relationship is parent-child.

Q: Does composition hurt performance compared to inheritance?

A: No, composition doesn't negatively impact performance. In fact, modern React optimizations (React.memo, useMemo) work better with composition because the dependencies are explicit in props and hooks, making memoization more effective.

Q: What about the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) in React?

A: LSP comes from inheritance-based OOP. In React, you achieve similar benefits through composition—components with compatible prop interfaces can be used interchangeably, but without the tight coupling of inheritance.

Questions? Share your composition patterns or scenarios in the comments below. Which pattern do you find most useful in your applications?